[Tratto da: La Biblioteca del

Piccolo, [data?]

p. 27-29.]

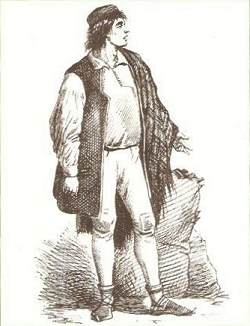

The ciccio came from the mountains, from burnt and barren lands crossed only

by flocks of sheep and lambs and he was a Slavic [no,

slavicized Romanian] mountaineer with wide-brimmed hat, sleeveless chestnut grey

overcoat, tight grey trousers, white and flat slippers called opanche. He was

said to come from Cicceria or from the "land of the Cicci", locating this

plateau in the upper part of Istria, an area high above sea level and rich in

woods from which the cicci drew large quantities of firewood and soft coal .

The appellative cicci used to indicate the Romanians of the Carso, just as

cicerani

or ciribiri indicated those under Monte Maggiore, berchini those of the

Castelnuovo district, besiachi the Croats, fucki the peasants of Pìnguentino,

bodoli the islanders of Quarnero and maurovlahi the Dalmatians from the

mountains from the Poreč or Polesine countryside.

The figure of the ciccio

|

|

Above and on the right, a ciccio and a ciccia from the series of costumes and

trades by Eugenio Bosa. |

|

|

The ciccio arrived in

Trieste carrying with him heavy sacks containing the goods

to be sold, i.e. bundles of wood and soft coal. Shouting "Carbuna! Carbuna!

Fassi!" the

Trieste housewives flocked and the

ciccio began the sale, showing

them small samples of the various types of wood. Strong, resistant to cold, heat

and hunger, the ciccio reached the market squares, overcoming many difficulties

and remained there only for the time necessary to sell his products, to then

return with the small profit to his house hidden among the mountains. The Ciccio belonged to those Slavic[ized] Istrians who loved their

domestic independence, people who did not want to practice arts or professions

of any kind, but to continue the trade of their ancestors, handing it down from

generation to generation. In fact, they did not alter the uses and customs of

their own race, they never dressed, not even in winter, their right arm, which

remained covered only by the sleeve of the shirt, almost giving the impression

of being about to fight or ready for flight.

The ciccio arrived in

Trieste carrying with him heavy sacks containing the goods

to be sold, i.e. bundles of wood and soft coal. Shouting "Carbuna! Carbuna!

Fassi!" the

Trieste housewives flocked and the

ciccio began the sale, showing

them small samples of the various types of wood. Strong, resistant to cold, heat

and hunger, the ciccio reached the market squares, overcoming many difficulties

and remained there only for the time necessary to sell his products, to then

return with the small profit to his house hidden among the mountains. The Ciccio belonged to those Slavic[ized] Istrians who loved their

domestic independence, people who did not want to practice arts or professions

of any kind, but to continue the trade of their ancestors, handing it down from

generation to generation. In fact, they did not alter the uses and customs of

their own race, they never dressed, not even in winter, their right arm, which

remained covered only by the sleeve of the shirt, almost giving the impression

of being about to fight or ready for flight.

In

Trieste, the

ciccio was well liked and accepted, although his activity was

considered very humble by the people of

Trieste, perhaps the humblest of those

then exercised, so, with that witty and biting spirit that has always

distinguished the people of Tergesto, the people of

Trieste ironized a a little

about cicci and Cicceria and, having to give a negative judgment on a person

deemed incapable, they used to say: "Va la, bon de niente!

ciccio no xe per barca!", with a saying still very much in use today.

The ciccio carried out his business in that era that knew neither gas, nor

electricity, nor heating systems in houses, but only

fogoleri,

stue e forni a legna per la panificazione domestica.

The Slavic [Romanian] mountaineer sold coal but also wooden hoops,

handcrafted in winter; sometimes he was accompanied by a ciccia, his wife. The

woman carried large baskets full of vegetables, or wooden hoops on her

shoulders. The ciccia had a hemp cap on her head, opanks on her feet and

she wore a

knee-length overcoat that covered her heavy skirt and woolen socks.

The cicci were involved not only in the production of soft coal, but also in

sheep farming, in the transport of wine, salt and oil from the coast to the

inland areas of Carniola. The figure of the ciccio now belongs to another era,

almost to another world, the one in which our grandmothers and

great-grandmothers were intent on putting le spizze nelle stue (stoves) and

"sufiar su le bronze" because "el fogo ciapi" the

firewood, a world in which our

grandmothers and great-grandmothers ran swiftly into the street shouting:

"Carbuna! Carbuna e fassi!".